The Not-So-Sweet Sugar Wars, Then and Now

On Sept. 28, workers at the Rogers sugar refinery in Vancouver went on strike.

Within weeks, bakeries told media outlets they were running out of sugar and supermarket shelves were sometimes bare. Lantic Inc., which owns the refinery, has kept it running with a skeleton crew of managers, but at a fraction of its capacity.

Many shoppers across Western Canada might have been out of luck.

Unless they happened to find Tiger Sugar.

Plastic packs of the new brand began appearing in some Save-On-Foods locations, often on the shelves where white bags of Rogers Sugar might have been.

Shoppers wouldn’t have recognized the brand. That’s because Tiger Distributors Ltd., the company that packed the sugar, was founded on Sept. 29, the day after the strike began.

According to the provincial business registry the company’s sole director is Ashok Aggarwal, whose Surrey family owns other food companies. Requests for comment to Aggarwal were not returned.

Adrian Soldera, who leads the union local that represents the striking refinery workers, noticed the new brand along with others that have popped up on shelves with sugar sourced from Thailand and beyond.

“We’ve been noticing all kinds of companies coming out of the woodwork now,” said Soldera, president of Public and Private Workers of Canada Local 8. “There’s lots of sugar out there on the market.”

Since the start of the sugar business in Canada, a handful of companies have controlled domestic sugar production, sometimes with the tacit blessing of courts and government.

Which is why a strike at one refinery could create shortages, entice new companies to enter the market and disrupt access to something as common as sugar.

Building a sugar empire

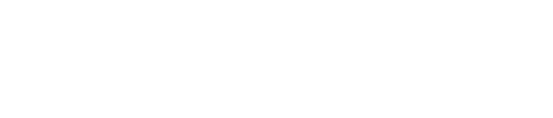

When B.T. Rogers built his Vancouver refinery in 1890, it was one of a handful in Canada.

“When Rogers was established in 1890, Vancouver was only just starting to industrialize. There was a lot of investment coming from Montreal and New York,” said Donica Belisle, a history professor at the University of Regina who has researched the history of Canadian sugar and written a coming book about its links to indentured slavery — Canadian Sugar and Indian Indenture in Colonial Fiji.

It helped that some investors in the newly completed Canadian Pacific Railway were also investors in Rogers Sugar, eager to have customers for the rail line establish in Vancouver.

“They saw it as connected, because Rogers would send its sugar out on the rails through Western Canada,” said Belisle.

From the start, Rogers was one of just a few players in the domestic sugar market. Over time, that market only became more concentrated.

Belisle said Rogers was notorious for his business acumen and ruthlessness, setting deals with wholesalers to buy only his company’s product.

“Canada’s sugar market started out small,” said Chris Willmore, a historian and associate teaching professor at the University of Victoria. “And we kept giving them reasons to keep it smaller.”

Willmore, who holds a PhD in economics and has studied the early history of the Canadian sugar industry, said that eventually the small number of sugar refiners and wholesalers began collaborating to effectively fix prices.

“This is where the refiners saw they could essentially control the entire sugar trade, because they could set the price they want and the wholesale grocers would sell it on a cost-plus basis on a known formula,” said Willmore.

In 1910, the Canadian government took wholesalers to court in an early test of the country’s antitrust laws. But the judge dismissed the case, in part because he found there was no evidence of harm to the public.

“Once you have the judge come in and say this is A-OK, the wholesale grocer’s guild became bolder,” Willmore said.

The government tried again in 1920. A newly established Board of Commerce aimed to set a maximum price for sugar in a bid to tackle price-fixing. Refineries responded by shutting down their operations entirely. The board’s order would be in effect for a single day before it was suspended.

Those businesses would deny they held a monopoly. In a 1920 article entitled “Secrets of the Sugar Famine,” Blythe D. Rogers, who inherited his father’s company, would claim it controlled only the sugar trade in Western Canada because of how freight rates were set by the Canadian government.

But Willmore said the combination of price-fixing, tariffs on imported refined sugar and the failure of the government to tackle the monopoly gave Rogers a massive share of the business. Willmore added that the comments of the younger Rogers amount to a confession. “This is the next best thing to getting a necromancer and talking to him yourself,” Willmore said.

Today, Lantic Inc. and competitor Redpath control virtually all domestic sugar production. There are few restrictions on importing refined sugar. But Willmore said the barriers to enter into domestic production are substantial.

“If you wanted to start up a new sugar refinery in Canada, there would be a whole lot of startup costs and costs to starting relationships that the existing companies had already made,” Willmore said.

Unless, of course, there was suddenly not enough sugar to go around.

The great sugar strike

Rogers continues to make sugar in the same big, grey refinery built in 1890. In a given year, Soldera said, the facility produces between 150,000 and 220,000 tonnes of sugar a year.

But today the refinery is producing a fraction of that. More than 130 members of PPWC Local 8 have been on the picket line for nearly three months, leaving refinery operations minimal.

In its latest quarterly report, Lantic Inc. estimated the Vancouver refinery was producing about one-third of its typical capacity.

Martin Barnett is executive director of the Baking Association of Canada, which represents roughly 600 member bakeries across Canada.

Many members had worried about access to sugar, he said.

And while shortages have eased, Barnett said, the media coverage of the strike may have inadvertently made the shortages appear even worse than they were.

“There were a few days there, on and off, where sugar was rationed by local distributors. And that made people nervous so they were running out and buying as much as they could when they could get it. And that kind of exacerbated this situation as well,” Barnett said.

“Our suppliers were saying, ‘We don’t know what’s going on. We cannot guarantee we can get you that container.’”

Meanwhile, the two parties at the bargaining table appear far from a deal.

Soldera said the company and union traded proposals last week, with the major sticking point being the company’s request to introduce weekend production and 12-hour shifts. The plant now operates around the clock Monday to Friday.

The union has rejected that request, arguing the company should hire more workers if it wants to increase its production.

“We’ve maintained that if they hired more staff, they could do these run-through weekends when they need it,” Soldera said.

Soldera said the company and union were set to sit down with a mediator on Dec. 13 to discuss a potential deal.

But, Soldera said, the company withdrew its proposal, saying there would be no agreement unless the union agreed to the longer shifts.

Soldera said the company also sent its proposal directly to union members, violating the labour code. The union has filed an unfair labour practice complaint to the BC Labour Relations Board.

The company then issued a press release on Dec. 14, saying the union had “rejected” its latest proposal.

“Given the union bargaining committee’s current position, at this time we are pausing negotiations,” reads a statement sent by Jean-Sébastien Couillard, the company’s chief financial officer. Couillard said the company did not wish to make further comment.

Soldera said union members remain committed to the strike. An online vote last week, he said, found 89 per cent of responding members were in favour of continuing job action.

But he also said he knew some members had found other jobs, unable to make ends meet on strike pay.

“I know some guys have had to go out and find work. They have to look after their families,” Soldera said.

The strike has also stung the employer. The company has tried to offset the impact on major customers by diverting sugar from another refinery it owns in Alberta. The union, though, has threatened to picket businesses that receive that sugar, and won commitments from major companies not to buy that product.

While the company says it can weather the strike, it acknowledged in its report that it is affecting its bottom line.

“This labour disruption is expected to negatively impact our financial results for 2024, the extent of which is not yet known, and will depend mainly on the length of the strike, and the potential internal incremental costs associated with servicing our western customers impacted by the labour disruption,” the report said.

In some ways, history is repeating itself.

In 1917, more than 200 workers at the facility walked off the job after they said one of their colleagues was unfairly dismissed. The strike would last 92 days.

In 1911, the Victoria Daily Times ran a story titled “Alleged Baking Horrors in City.” It was about long hours in the Rogers Sugar refinery. The article suggested the workers transition to an eight-hour work day.

By Zak Vescera, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter