Nation-state independence and the state of happiness

Scotland’s Referendum

Readers will be aware of the story last week of Scotland’s independence referendum. The “yes” side lost its bid for an independent Scotland, as Quebec’s yes side has lost in two recent referendums, whereas Ireland succeeded — for 26 of its 32 counties – in seceding from the United Kingdom.

I feel Scotland’s story calls for historical context, with parallels to Ireland and Quebec. How does history shape how we feel about the kind of state we want to live in?

The ethnic and cultural roots of the Scots

There are four root stocks of Scotland’s people: Celts, Scotti, from north-east Ireland, who gave the name of Scotland to the nation; Britons from the Celtic stock of Britannia, the people in the land when the Romans came in the first century BCE; Picts, the picti or “painted ones” who fought the Romans and ruled so much of the land before the Scotti arrived in the west; Germanic peoples, mostly Angles, from across the North Sea. Each of them had monarchies, and the four stocks united would have just one monarch by the medieval era. A strong mix of Danish and Norse blood came into Scotland too, especially in the many islands north and west of the mainland.

Kings, Queens, and Nations

Like many medieval nations, the Scots were made by their monarchy. After Scots and Picts merged their thrones in 843 CE under Kenneth MacAlpin, Scotland pushed east and south against its borders, fighting Britons, Germanic invaders, and Scandinavians. Just as England was united by the family of Alfred the Great, by the year 1,000 there was only one royal family, and when the Normans conquered England in 1066, the King of Scotland was Malcolm Ceann Mhor, Great Head.

He and his brilliant wife “Saint” Margaret, an Anglo-Saxon princess of Alfred’s line, made Scotland strong enough to fend off the Normans. They did it by inviting some Normans to take feudal estates in the lowlands of south and east Scotland. Thus, Scotland added a mixture of Normans with the four older stocks. The highlands remained much more Celtic/Pictish, developing the clann system, while the lowlands, more populous, prosperous, and modern, were clearly unlike the highlanders by the end of the medieval era. Kings of Scotland were disturbed by this deep divide in the realm.

The Irish Parallel: too many kings, not enough community

A useful comparison to Scots unity under one monarch, is Irish fragmentation. Ireland had a theoretical single monarch, the ard righ or high king, but in fact the Irish Celts never had a king with effective power over all the island. The Vikings came to disrupt the Irish first, but the real end to any hope of an Ireland united under a king of Celtic stock came when the Normans came from England after 1166 CE, and the English monarchy took over rule of the island – or as much as was possible given their many other foreign wars in the Middle Ages against Wales, Scotland and France.

Celtic law, or Brehon law, the old Gaelic Irish language, rural culture and semi-nomad economy, were all very much out of harmony with Anglo-Norman feudal culture in medieval times. The Normans did assimilate culturally by marriage with the Irish Celts; great lords such as the Fitzgeralds and Butlers dominated vast territory, outside royal control.

Despite incessant petty baronial feuds and wars, at least all inhabitants of Ireland shared one Catholic Christian faith, sparing Ireland the horror of religiously-enflamed warfare. This fact of religious unity lasted only until the 1500’s. After that, the Protestant monarchy of England became ever more a conquering foreign power in Ireland. Elizabeth I and the Protector Cromwell waged terribly destructive wars in Ireland. Each defeat of the Irish meant dispossession of their lands.

The final conquest of the land for Protestantism, English law and landholding, came in 1692 under William III. Thereafter, for a century, Ireland lay miserably subjugated by the English, who had their own Parliament in Dublin where Catholics were banned as MPs and as voters. This was the awful nadir of the Irish under the Penal Laws. By comparison, after the 1707 Acts of Union between Scotland and England, Scotland was not so horribly oppressed by English power. It helped a great deal that most Scots were Protestants of the Church of Scotland, the Presbyterian Church.

Scotland united to England

Scotland fought the English kings who invaded from the time of Edward I, who conquered Wales, through Edward II, defeated by Scots at Bannockburn, Edward III conqueror of half France, and up to the Tudor monarchs of England. The War of Independence for the Scots was a glorious event creating a sense of nationhood that might not have come without the hammering England delivered to the Scots for 200 years. Religion then took a hand, by giving Protestant England and Scotland a very important common denominator, fear of Roman Catholicism.

A Scots royal dynasty, the Stewarts (also Stuarts), took the throne of England in 1603 due to the accidents of family marriages and lack of an heir for the Tudors. James VI was king of Scotland from his infancy but only took the crown of England in middle age, hoping to convince all his subjects that “Great Britain” should be the result of one monarch on the two thrones. His dream died with him, and his son lost his head, literally, by fighting the Scots and English Parliaments in the Civil War.

England conquered Scotland for a brief time under the Protectorate of Cromwell, who created a republic – called a commonwealth – uniting the English, Scots, Welsh and Irish with just one parliament in London. His death returned politics to the pre-civil-war norm, and two more Stuart kings ruled the three kingdoms with three parliaments. The second of these kings, James, was put off his throne because he was Catholic and suddenly produced a son. England’s Protestant ruling class rebelled and asked William, prince of the Netherlands, to come and take the throne in 1688. He did.

William III and his wife Mary Stuart, and her sister Anne, were champions of Protestantism against the power of Catholic France. Queen Anne, fighting a great war with France, wanted to ensure her English kingdom against a possibility of a hostile Scots king inheriting the crown of Scotland. Anne would die without an heir to either throne, causing the English throne to go to a German dynasty, still on the throne today as the House of Windsor. It seemed not unlikely that the Scots’ throne would go to a different royal family at her death. Anne and her ministers made a pact with potent Scots lords to dissolve Scotland’s parliament forever and unite the two nations with one parliament in London, with a law forbidding the throne to ever pass to a Catholic. The Acts of Union in 1706/07 did that; Scotland got 16 peers in a House of Lords with 190 seats, and 43 MPs in the Commons where over 500 sat. Scotland’s voice would be very feeble in this Union Parliament.

This Union is what the Scots were trying to end with their referendum last week.

Canada becomes British, and the Quebec canadiens become a minority

Canada was French for 150 years before it fell to British conquest in 1763, and until 1867, Quebec was a Province in the British empire, with differences that worked to its disadvantage – its canadien people spoke French, their religion was Roman Catholic, and their culture seemed peculiar to the English, especially their lack of commercial economy and their particular legal system.

British rule in Quebec was based on pleasing the key social classes – the clergy, the landlords, and a commercial class which was in fact mostly English and Scots. The mass of the people, francophone Catholics, had a population explosion but lacked a political system in which their majority numbers would be self-governing. The republican USA was a nearby example of democracy for canadien popular leaders, who wanted to leave the empire, leading to a failed rebellion in 1837-38. Extreme

British violence against the rebels increased feelings that independence would be best for Quebec.

The Province of Canada, existing from 1840 to 1867, united Quebec to Ontario. Democrats in both halves of Canada fought for “responsible government” – a guarantee that the majority party in the provincial Assembly would rule the Province. The forced marriage of the English province with the French one had severe political problems, to which the solution was a federal state created by Confederation; Quebec got provincial power over many significant aspects of its local affairs.

Tragic Ireland, rising up, smashed down

In the long wars fought with France after its Revolution began, and under the rule of Napoleon, Britain suddenly united Ireland with itself, ending the long independence of the Dublin parliament. By the Act of Union of 1801, the independent institution Ireland had enjoyed since 1297 CE, its Parliament, its houses of Lords and Commons with a monarch who also sat England’s throne, was erased. England did this because of fear of Ireland as a base for foreign enemies, since France (and Spain before that) had tried several times to interfere in Ireland. An Irish Revolution in 1797/98 was put down with great brutality by Protestant forces; one small part of Ireland in the northeast was heavily populated with Protestants, a majority from Scotland, and this area (“Ulster”) was also the area which underwent the Industrial Revolution while the rest of Ireland was pastoral and poor.

The Irish Famine from 1845 to 1849, created a symbol of English misrule that would never be forgotten by the Irish political leadership who wanted a republican Ireland. Republican rebellions against England in 1848 and 1867 were quickly crushed by British soldiers and police. Meanwhile, some Irish leaders believed that parliamentary methods would bring Ireland good government and a sort of “home rule” — designed similarly to Canada’s autonomy in its domestic affairs after 1867.

The revolutionary and the evolutionary tracks of Irish political independence movements competed until WWI, when the one successful Irish revolution began with the Easter Rising of 1916. Ireland became the “Irish Free State” within the empire in 1922, after a nasty guerilla war with England in 1919 – 21. It developed a Constitution by 1937 that made republican government without the name, and the recognition that it was in fact the Republic of Ireland came in 1949. Still, six counties of Ulster are to this day united with England, Scotland, and Wales in the United Kingdom. Ireland is an example of a single island where two ideas of the best constitution share the political sphere. It may yet resolve this duality by a federal system, as we in Canada dealt with our differences in 1867.

Imperialism rewards Scottish entrepreneurs and emigrants

Some Scots were thriving after the Union with England in 1707. Industrial capitalism came to the Scots as to the English, earliest of all nations on earth. David Hume and Adam Smith were great names in the evolution of British thinking about politics and economics; both were Scots. The Scottish Enlightenment was an astonishing intellectual achievement that impressed England too.

Yet, while great capitalist entrepreneurs rose among the Protestant Scots of the lowlands, the Catholic Highlands languished in poverty and more primitive social order. The greatest military threat to England ever in the 18th came from a Scots invasion led by Charles Stuart in 1746, and his power in Scotland was drawn from the highlands. After his utter defeat at Culloden, Bonnie Prince Charley was finished, and the clan system of the Celtic region was subjected to the modernism of a capitalist ruling class. The highland clearances began when the clan chiefs converted their titles to communal land into private property and made the peasantry leave in huge numbers, to go on ships to America and Canada by disease or suffer in new industrial cities like Glasgow and Manchester.

Scots did very well in America, and in Canada. As political chiefs or economic wizards, they were thriving. The peasantry took land and became farmers with more opportunity than ever offered at home; Irish peasants too prospered in the New World, although Catholicism was still a handicap in the Protestant English world of Canada.

Summing Up: What do “nations” want?

In all the foregoing outline, it must be clear that I avoid the concept of a “nation” in any sense that a nation is the natural demographic foundation for a State. I did that deliberately.

If one paid attention to the Scots who spoke about independence, it was notable that leaders tended not to say a great deal about the meaning of Scottishness. The very concept of nation underwent an intellectual rebirth when democratic forms of government and cries of “Liberty!” became popular.

The Americans birthed a democratic form of state in 1787 in their Constitution, but the English and the Dutch too had evolved democratic forms, anti-monarchical and anti-aristocratic, from about 200 years before that. Englishness, Dutchness, Americanness, were not key to their democratic ideals.

It was the Revolution in France, not in America, that truly began to articulate the quasi-mystic ideal of a Nation. A Nation has a “character, or genius, or destiny”, in this kind of thinking. All through the 19th century, philosophers of nationalism used language like this, and every European people that wanted “freedom” spoke about the special qualities of their nation.

Canadians, and Americans to a lesser extent, do not respond well to the metaphysical and intellectual phrases tossed around when Nation is discussed by Europeans. We are not a Nation in that sense because we came into being by immigration. We do not have the ethnic roots nor the unitary history of a nation like the French, Spanish or Germans, to give us a national identity.

We are now quite proud of that. We are a nation of immigrants. According to an act of Canada’s Parliament passed in 2006, there is a nation called the Quebecois. [“That this House recognize that the Quebecois form a nation within a united Canada.” is the wording of the resolution passed on November 27th that year.] So, if there is a nation called the Quebecois, is there a nation called Canadians? I really don’t know. There is a state called Canada, and there are Canadian citizens, but do not ask me what my nation is. I do not feel I have one. My roots are definitely W.A.S.P. though.

Scots chose not to create an independent Scotland by ending the Union with England, last week. They too are modern, like we Canadians. They know “Scottishness” is not a compelling reason to make a new state. The Yes side made several arguments. The reasons were economic, political, and social. They wanted more properity from their land’s resources and less dominance by foreign capital. They wanted less control of their politics by people living far away in London. They often said they wanted social justice. To me, a lifelong socialist, that means combating the inequities of wealth and privilege that are the lifeblood of capitalist society.

In the end, what one wants from the state one lives in is a very individual motive. The Yes side did not appeal to enough individuals with a collective vision of a better life for each person, if Scotland were independent. Quebec, with its wide provincial power in a federal system, has created a province unlike any other in Canada, with better programs such as childcare and low university tuition, and I envy people there for that. Would my life be much better there? No, that is why I stay in BC.

Scots asked themselves about a new state that does not exist yet, and answered No. The imagined future state is a mirage. It might be better, or worse, or about the same. You have to be a very convinced person to feel you know the future will be better. In Scotland, a majority decided they did not have that faith, that the changes that might come would be beneficial and revolutionary.

Still, 45% had that faith. I would argue that that is a very big fraction, and demands another referendum in the next decade to ensure that the decision to stay in the Union is the wise choice.

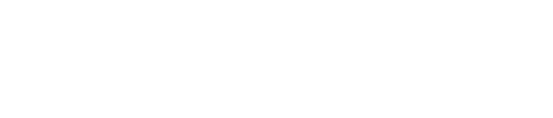

Charles Jeanes is a Nelson-based writer. The previous edition of Arc Of The Cognizant can be found here.