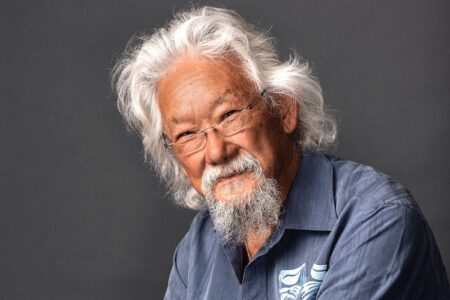

UN advisor returns to Kootenays from Rio with new hope for local solutions … and little faith in global ones

United Nations trade and climate change advisor Aaron Cosbey—a Rossland resident—attended the first Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, and he was back again last week for the glitz, fanfare, and “complete failure” of the Rio +20 anniversary conference.

“It was a very predictable thing,” Cosbey said, listing many reasons the world’s governments failed to negotiate any meaningful agreements under the broad scope of “sustainable development.”

“It was like watching a train crash in slow motion,” he said. “You could see it coming, you could watch it happen, and there it goes—it happened.”

“Can they ever do one of these again, a ‘Rio +50’ or whatever it’s going to be next?” he asked. “I think these conferences should be banned henceforth. They’re a colossal waste of time and money. I really hope this is the last of the mega-conferences that we ever do.”

Far from dwelling in doom and gloom, however, Cosbey said the utter failure of governments to “understand how urgently we need action” is only one side of the Rio +20 coin.

“There are two very different dynamics at these summits,” he explained. “There’s the formal negotiating process where governments sit down together and try to hammer out a final agreement according to an agreed-to agenda—but then, on the side, there’s a gathering of the clans.”

“All the people that are working on sustainable development issues get together because they know all the others working on these issues are also going to be there,” he said. “This is their chance to show people what they’ve been doing over the last year or plan to do over the next year. They roll out new ideas they’ve had and look for others to cooperate with. It’s an efficient way to meet with all these people without actually flying to their place.”

“That’s the exciting part, that’s the only reason I go,” he said. Cosbey has returned to the Kootenays reinvigorated and revitalized. “I’m pumped about the connections I made while I was down there, and now I’m working on some of that stuff. I’m delighted.”

The negotiations themselves are “boring,” he said, and mostly closed. “Even though I was representing the UN, there were a lot of those meetings I couldn’t get into either. You can follow them from a distance because you don’t have any impact on them anyway.”

By contrast, civil society at Rio +20 was humming at every moment with as many as 6 or 7 concurrent events put on by NGOs (non-governmental organizations), businesses, and research institutes pulling panels of speakers together “to talk about the cool stuff they’re working on,” Cosbey said.

“It’s the paradox of Rio,” he said. “You have this terrible result from the intergovernmental process, and it’s depressing: the governments of the world can’t can’t see beyond their next election prospects to take some kind of leadership role in fomenting action.”

“At the same time, in the shadow of that depressing news, there was so much great stuff going on at Rio. It was all stuff that businesses were doing, that municipalities were doing, that NGOs and groups of NGOs were doing—there was all this beautiful creative energy around small solutions to focused problems on sustainable development,” he said.

“I believe progress takes place in little steps by little people—lots of them doing stuff. I don’t believe it takes place as a result of grandiose declarations of intent by governments,” he said. “[Sustainable development] could be happening a lot better, a lot faster, and a lot more broadly if governments got on board—but unfortunately they’re not.”

Examples of “great stuff” included some businesses producing juice from a plantation in Mata Atlantica’s endangered forest. “They’re doing so in a way that actually regenerated forest and provided an income for local indigenous populations—and it’s a highly successful consumer product in Brazil,” Cosbey said. “The idea is that they should be able to do sustainable business and make it pay. Not only that, but they had created a coalition of businesses from around South America and beyond trying to commit to the same principles.”

Closer to home, one presentation described cattail harvesting from the Lake Winnipeg basin. Cattails suck up the excess phosphorous in the watershed due to the intensive use of synthetic fertilizers by surrounding farms. The cattail biomass is burned in boilers, replacing fossil fuel, and the phosphorous-rich ash can again be used as fertilizer.

For Cosbey, these and other examples show how we can “find ways to make decent jobs for people that actually have environmentally nice outcomes and make people better off.”

Back up at the global level, however, it doesn’t look so good.

“I know a lot of people are depressed,” Cosbey counselled. “I was really depressed after the climate conference in Copenhagen in 2009—I had actually expected an agreement from the governments there and came away thinking, ‘the process is dead.’ This time I went into it knowing there would be no agreement.

That’s not how it was back in 1992 when Cosbey was a “young’un” manning the booth for the International Institute for Sustainable Development, a Canadian NGO based out of Winnipeg. He describes his younger self as “jaded,” even then, about the prospect of meaningful global agreements being carried out, but the differences between then and now are nevertheless “huge.”

“In ’92, the governments of the world understood it was time for action,” he said. “There was political momentum behind the concept of sustainable development. There was readiness to move, even among recalcitrant countries like the US. Certainly Canada was on board.”

“At that time, Canada was seen as a champion of sustainable development. These days, Canada is seen as an absolute pariah on the international stage.”

Cosbey couldn’t help but note that Canada recently ranked 51 of 89 countries in world rankings for government openness “behind such luminaries as Uganda and Niger.”

Back in 1992, Cosbey described the secretary general of the conference, Maurice Strong—incidentally, a Canadian—as “amazing,” engaging in “shuttle diplomacy” among world governments for years leading up to the conference.

“[Strong] orchestrated a process that was brilliant—he worked from the grassroots as well as from the top down,” Cosbey said. “He convened a machinery of bureaucracy to try to do pre-negotiations and get agreement among governments on process and substance. He led a beautiful grassroots effort that got input from average citizens around the world leading up to regional meetings, leading up to international meetings, all feeding into this final process.”

And, Cosbey said, the final outcomes were “impressive.”

Earth Summit outcomes included the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, “the only international agreement on climate change.” Most nations agreed to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, “another one of the big six or seven multilateral agreements on environment,” Cosbey sid. On the same lines, most nations agreed to the Statement of Forest Principles.

That wasn’t all. One hundred and eight heads of state attended the summit, and the 172 participant nations all signed the 27 principles of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, which enshrines such sustainable bedrock as the precautionary principle and the polluter pays principle.

And there was Agenda 21, recently “banned” by the State of Alabama for allegedly tromping on the sovereign rights of property owners as part of a sinister UN plot to establish a single socialist world government at the expense of America’s hard-won and constitutionally guaranteed freedoms.

“It’s a crazy world,” Cosbey laughed, admitting that “‘Agenda 21’ does sound like a B-movie plot to take over the world.”

“Enthusiasm for sustainable development waxes and wanes,” he explained, and there was a peak around 1992, perhaps coming on the heels of 1987’s groundbreaking Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, “a really excellent report that coined the term ‘sustainable development’ and built a groundswell of public, grassroots support for the idea,” Cosbey said.

Globally in 1992, he said, “there was an overarching agenda for sustainable development that spanned everything from international trade to water to communications to openness to natural resource management. There was a general understanding, back than, that we needed to do better.”

“There was another peak around 2007,” Cosbey said, as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released their seminal report, Al Gore released An Inconvenient Truth, and other events such as Hurricane Katrina’s devastation combined to create “political will.”

The contrast with 2012 is stark.

“This time, there was no single compelling reason for the governments of the world to come together in the first place. The only thing was the 20th anniversary: ‘Let’s have a meeting.’ That’s a bad basis for a starting point,” Cosbey explained. “There was no compelling amount of political will for sustainable development in a lot of governments.”

For example, Cosbey said, “Europe, the traditional champion of sustainable development, was focused on its own internal crises. Canada, of course, was absolutely absent from the team—they were, in fact, blocking progress. The US was mired in it’s own internal politics.”

Many developing countries, Cosbey continued, “were angry that the implementation of the stuff agreed to 20 years ago hasn’t happened yet, and they were unwilling to make a lot of concessions or agreements to go any further.”

It gets worse.

“The guy in charge of process, unlike Maurice Strong, was an absolute idiot,” Cosbey said of the Rio +20 secretary general, Sha Zukang. “[He] had absolutely no vision for the conference, no technical skills, and didn’t undertake any diplomatic efforts to try to bring about a desire outcome—because he had no desired outcome, really.”

Usually there will be at least a year, if not more, of preparatory processes leading up to that summit, Cosbey said. Small negotiations get more and more focused on final results as you approach the due date—but not so for Rio +20.

“The host country government, Brazil,” Cosbey added, “[acted] like this was really a non-event, like a warm-up for the Olympics [that Rio will host in 2016] or the World Cup [that Brazil will host in 2014.] They didn’t undertake the political efforts that you need to make one of these conferences successful.”

“All of that added up to complete failure,” Cosbey concluded.

When will the world get it together on an international agreement, for example on climate change?

Cosbey replied, “Even on a more focused issue, like climate change, you’ve got to wonder if it will ever coalesce as an international agreement, or if we’re going to be stuck with national and regional level initiatives going forward. At the international level, it’s going to take—I think—some horrible crisis to make countries actually wake up to the urgency. It’s a depressing prospect.”

Nevertheless, the struggle continues—it’s just that we can’t rely on governments to create the needed change, Cosbey suggested.

As an advisor to the UN Conference on Trade and Development that helps developing countries in trade and investment—”It’s supposed to be a counter-voice to rich country clubs like the OECD [Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development]”—Cosbey described the breadth of work before them, from “how to keep trade agreements like the WTO [World Trade Organization] and NAFTA [North America Free Trade Agreement] from screwing up the environment and screwing up third world development prospects,” to “working on trade and climate change, investment, green industrial policy,” and other elements of sustainable development.

“Sustainable development is so broad, it goes across everything,” Cosbey said. “Officially it’s about marrying the desire for increased human well-being, and environmental integrity, and social values. There’s not much that doesn’t get involved with that. It’s all of our economic activity, and it’s all of the environmental impacts that it has, and it’s all of the social conditions that are a result of the way we set up our societies.”

Two initiatives are of particular interest to Cosbey. One is to try to use trade regimes like the WTO to get rid of fossil fuel subsidies.

“Governments are spending upwards of $600 billion each year to subsidize the consumption of fossil fuels,” he said. “That’s a massive, massive force pushing us in the wrong direction.” Consequently, driving for positive, sustainable change becomes “like trying to hit the accelerator while someone’s got the parking brake jammed as hard as they can get it. You have to get rid of parking brake first.”

Another initiative is the idea of “border carbon adjustment,” Cosbey said, describing a recent case where the EU put in place an aviation carbon levy based on the distance travelled by airlines taking off or landing in the EU.

“They’re trying to bring the aviation sector within the carbon regime because it’s exempt from the current UN Convention on Climate Change,” Cosbey explained. But the result was a “firestorm of protest” against tariffs based on distance travelled outside EU jurisdiction.

“Other countries of the world were indignant that the EU took this unilateral, extra-jurisdictional initiative,” Cosbey said. Now the tariff has faced challenges in European courts—where the EU decision was upheld—and will soon be challenged by the UN International Civil Aviation Organization, and eventually the WTO.

Cosbey feels the issue speaks more broadly to “work on tools that happen on the border, but dictate what should be happening outside of the border.” He said we need to consider tariffs on goods from countries that don’t have adequate climate regulations, “to try and level the playing field with domestic producers saddled with the costs of climate regulations.”

Although Cosbey’s key to sanity at Rio +20 was “not expecting a great outcome from the world’s leaders when I went in,” he said, “we still need governments to get on board.”

“I tend to see climate change as one of our biggest challenges—there are several really big challenges,” he said. “To address climate change as part of a broader framework, you have to send a signal that you’re committed at some point in the future to restricting carbon and greenhouse gas emissions. If you don’t send that signal to businesses and investors, they’ll assume it’s not happening.”

“We need a regulatory and policy environment that governments put in place. If governments aren’t going to price carbon, for example, you’re not going to get all those nice solutions to energy efficiency and conservation. If people don’t see there are going to be regulations in the future to make them do it, no one’s going to pioneer it,” he said. “There’s no money in that.”

“If [investors] don’t get the signals, they don’t make the investments, and you’re stuck with these installations that are taking a pathway to high emissions,” he said.

It’s a huge issue in Canada, Cosbey said, and the overarching problem is the lack of “regulatory certainty.”

“The thing [businesses] want is some kind of certainty. What’s it going to look like in 15 years or 30 years, so they can make their investments appropriately? For me, that’s the biggest thing Canada falls down on,” he said. “There’s nothing there.”

“You have to be sending a signal that we’re going to be entering a carbon-restrained world: ‘governments are taking it seriously, regulations are coming into place regardless of whatever happens on the international stage.'”

How does Cosbey’s community life in Rossland fit into this mess of national and international ineptitude, albeit lit by beacons of local ingenuity?

“Rossland in particular fits in perfectly,” Cosbey said. “As I said, the exciting stuff is happening at the local level. People identify a need, identify good stuff that can be done, and they just do it. Rossland’s Energy Diet, the Visions to Actions process, there’s a bunch of really good potential in Rossland to take the kinds of actions at the local level that fit right into the dynamic I’m describing.”

“There is going to continue to be a blossoming of that kind of [project],” Cosbey predicted, “in part because people see their governments not doing anything. In one sense it’s depressing, but in another sense it’s empowering: ‘if they’re not doing it, we need to take up the reigns.’ There’s a need, so people step forward, they become empowered, and they show others how they can do the same.”

“That’s a beautiful thing.”