It’s the economy, dippers

The NDP leadership race suddenly seems like a very long, drawn out affair. Initially, there was much outrage – especially from Thomas Mulcair – at the suggestion that the party go along with what Jack Layton seemed to want: an earlier leadership convention in January. But now many in the party, lead by Winnipeg MP Pat Martin worry that the party’s performance in the Commons is suffering because many of its strongest MPs are out of their critic roles and pre-occupied with the race.

A couple of polls suggest the NDP is slipping and the Liberals are gaining at their expense, with the pollsters musing about the impact of the race as well. One poll in particular should cause the party concern as it hints at a more serious cause for declining support: Canadians’ increasing worry about the economy.

In a Nanos poll of a week ago “jobs and the economy” (at 29.3%) pushed the traditional leading issue, health care, well down into second place (22.8%) And that concern for the economy was up 3% in a single month. It should be noted that health care almost never falls from first place – just once in my memory when it fell just behind the environment for a brief period.

While the poll did not probe the reason for the upsurge in Liberal support (tied with the NDP at around 27% while the Conservatives dipped under 36%) it seems reasonable to conclude that if people are concerned about the economy they go to the parties that have traditionally garnered more trust on the issue: the Liberals and Conservatives.

The economy will likely continue to be the number one issue for a majority of Canadians for some time to come. More people are more indebted than ever before, hundreds of thousands have mortgages in danger of default with a two or three point increase in interest rates, wage increases continue to lag behind inflation, unemployment and underemployment are still high, and the crisis in Europe and the weak US economy represent a major threat to the Canadian economy. And now more and more analysts are suggesting China it is headed for slower growth – which means lower demand for Canadian resources. This has not escaped the notice of Canada’s largest corporations, either. They are sitting on some $450 billion of cash that they show no sign of investing.

The NDP has always been skittish about the economy as an issue. After all, it competes politically in a capitalist world and the conventional wisdom is that the capitalist parties have the edge on how to manage the economy. But by avoiding talking about it (like they did even for – most – of the 1988 free trade election) the party continually reinforced the notion that it can’t be trusted on the issue.

The party always counted on its traditional issues to carry the day – Medicare, social programs, the environment, and education – policies that required robust, activist government. So long as government seemed able to provide for those things, the NDP held its own. But during times that either the Liberals or the Conservatives played the deficit hysteria card, they faltered, as they did in the 1990s when Paul Martin successfully cut 40% off federal social spending on the heels of a four year fear campaign about the debt.

In the last election the party ran on Jack Layton and broke through the wall of mistrust of government than characterizes the Canadian electorate. And in Quebec, he benefitted from that province’s long history of supporting a strong social role for the state. But Jack is gone, mistrust is back, and people are looking for reassurances that someone knows how to guide the economy.

There is no better time for the NDP to avoid its coy relationship with economic policy. The Occupy phenomenon highlighted the growing inequality that liberating the market has produced; the Harper government’s policies have been a complete failure (except briefly with a stimulus package forced on it by the opposition); the Liberal Party, despite the recent bump in the polls may well be terminal (see Peter C. Newman’s new book pronouncing it effectively dead).

Sunday’s leadership debate demonstrated that the party is finally getting it: it actually focused on the economy. But only two of the leading candidates – Peggy Nash and Paul Dewar – had released anything like economic policy statements before the debate. It would have been a lot more meaningful if the other candidates (Nikki Ashton also released an economic statement earlier) had their economic policies in place. It should not come as a surprise that Nash, finance critic until she announced her campaign, is leading in this policy contest. She has focused attention on reversing the ten year trend of exporting raw resources and returning to a value-added economy; fairer taxes; requiring companies to make binding commitments on jobs and development (that would violate NAFTA, but perhaps we should); massively increase public investment in the face of the private sector’s refusal to do so; strengthen income security programs that were decimated under the Liberals; and integrate and enhance social programs with a view to boosting jobs and productivity. She also calls for formal co-operation between government, business, labour and universities to guide a return to a comprehensive industrial policy – pointing to Finland, Korea, Brazil, and Germany’s successful approaches.

Paul Dewar’s plan – “Creating Good Jobs and Training for the Jobs of Tomorrow” – is thin and conventional by comparison. Calling for “Support for small and medium-sized businesses” is meaningless rhetoric. “Reinvigorated national training programs…” doesn’t mean much either if the private sector isn’t investing. He does call for a permanent infrastructure program and promotion of value added industries but so far with little detail. He promises to go after tax havens but says nothing about fair tax reform. In the debate he had no answers to Brian Topp’s question about where he would get the revenue for his program promises.

There is a long way to go for the NDP to establish itself as a serious contender for the ‘good economic manager’ title. One debate won’t do it. But if the other candidates take up the gauntlet thrown down by Nash, it could go a long way to breaking the 40 year taboo. The final outcome for an NDP economic policy needs to include, in addition to Nash’s points, a commitment to strengthen the domestic economy by ending the 25 year suppression of wages, a clear and detailed tax reform policy (Brian Topp’s strength at the moment) to increase government revenues; vigorous enforcement of labour standards to protect workers from ruthless employers; a national energy policy that places limits on tar sands expansion and puts current oil industry subsidies to work rapidly developing alternative energy sources, and lastly an acknowledgement that unfettered consumerism is an unsustainable economic policy. That means a shift away from private goods to public goods. Economic policy is seen as dull stuff, but there is no reason it can’t be visionary.

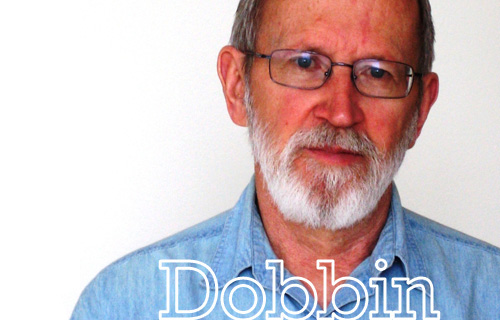

Murray Dobbin is an author, journalist, and blogger. This column originally appeared in his blog.